The Unsolved Puzzle Of How Mercury Can Even Exist

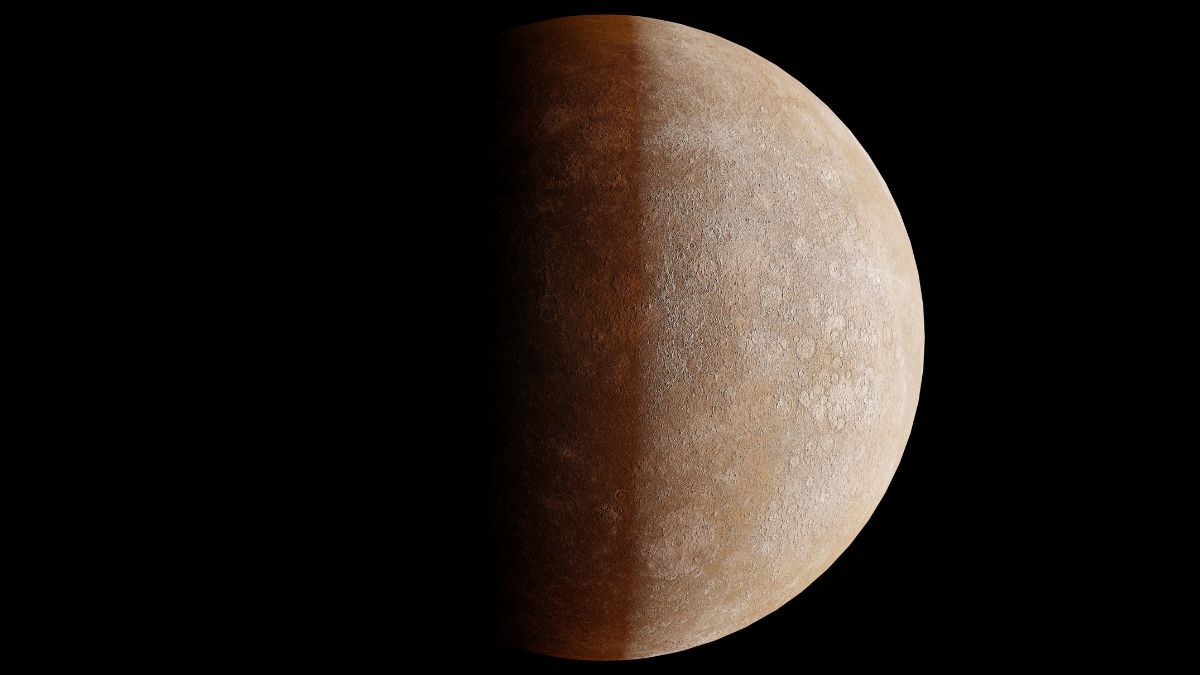

At first glance, the small planet nearest to the Sun appears to be nothing more than a scorched and desolate rock. It lacks the rings of Saturn or the potential for life found on Mars, yet this tiny world represents one of the biggest paradoxes in planetary science. Astronomers have struggled for decades to explain how such a celestial body could form in its current state. The planet is an oddity that defies the standard models of how our solar system came to be. Its existence challenges our understanding of the delicate processes that create rocky worlds.

The primary issue confuses scientists because of the extreme density of the planet compared to its relatively small size. Mercury is roughly twenty times less massive than Earth, but it ranks as the second densest planet in our neighborhood. This statistic implies that the planet is composed mostly of a gigantic metal core with only a thin rocky shell. A core of that magnitude takes up a staggering percentage of the planet’s volume and leaves very little room for a mantle or crust. This internal structure is unlike anything else orbiting our star.

For a long time, the prevailing theory suggested that a violent history shaped this metallic cannonball. Alessandro Morbidelli from the Côte d’Azur Observatory notes that the general interpretation involves a giant impact early in the planet’s life. This hypothesis proposes that a massive collision stripped away the lighter outer layers and left behind the heavy iron heart. Such a catastrophic event would mirror the theory of how our own Moon formed. Scientists accepted this violent removal of the mantle as the best explanation for years.

Data returned by the ‘Messenger’ mission threw a wrench into this widely accepted idea. The spacecraft detected high concentrations of volatile elements like potassium and sulfur on the surface. These elements vaporize easily at high temperatures and should have been lost completely during a mantle-stripping impact. The presence of these fragile materials contradicts the idea of a high-heat collision or a scorching formation process near the early Sun. This discovery forced researchers to reconsider the entire history of the innermost planet.

Modern research now looks to future missions to resolve these contradictions. Saverio Cambioni, a planetary scientist at MIT, suggests that Mercury is likely the closest analog to an exoplanet that we have available to study. Understanding this strange world is crucial for interpreting the data we receive from rocky planets orbiting distant stars. The ‘BepiColombo’ mission is currently en route to provide the detailed data needed to solve this riddle. Its arrival could finally explain whether the planet formed from a series of hit-and-run accidents or through a process we have yet to imagine.

The scientific community eagerly awaits the new data that might finally reconcile the heavy core with the volatile surface. Do you think our current models of solar system formation are completely wrong or just missing a piece?

Please share your theories on this planetary mystery in the comments.